From the archive: Household archaeology and the science of stuff

What do we uncover when peeling back the layers of a home?

For the second time in three years, I’ve been thinking about the layers of paint at my old house.

The mauve that covered every surface when I bought it 10 years ago, a relic of the previous owner that I spent hours trying to cover, one brushstroke at a time. The matte gray on the cabinets that I still love so much but exists now only in my photo roll and memory.

This time around, I’m at the end of a six-month, soul-searching ordeal that left me digging through someone else’s material culture — three truckloads of material culture — and led me back to this post from 2022 about the idea of household archaeology.

As I let the dust settle from this (hopefully) once-in-a-lifetime renovation, I wanted to re-share this piece that was also published as part of the 2024 summer zine, a print publication that is sent out to paid subscribers twice a year.

It’s a snapshot into the relationship that we have with stuff and the places we live.

This way of looking at this house — and the endless screws and bottlecaps and plastic toy pieces coming up from the yard, remnants of this terrible time that I know I’ll find for years to come — has helped me move through this season of restoration.

A reminder that I am not the first person to pay this much attention to these walls, that grass, those doors. And I won’t be the last.

Life is but a layered cake. Just like a house.

More soon,

Addie

Originally published July 21, 2022

It’s nearly August, and I’m still consumed by this move.

Because a move isn’t really just a move, is it? It’s a chaotic shift to our foundational that forces us to assess every single item in our homes and decide not just whether to move it, but where it should belong if we do and what should happen to it if we don’t.

It’s been seven years since the last time I dug through my possessions and spent so much time thinking about my resources, my values and my identity.

This time feels different because I am different.

During my last move, I was a newly divorced parent of two elementary school-aged children with no clue that my 30s would hold the loss of a parent, a change in my spiritual outlook and a departure from my traditional journalism career.

Now, I’m on the cusp of a new decade, a new marriage and several new careers that feel more like a calling than a job.

And yet here I am, scraping paint off the floor, wondering when I am ever going to feel truly settled again.

Because I’ve spent so many weeks with a paintbrush in my hand instead of a keyboard, I’ve had a lot of time to think about what happens when we peel back the layers of a home.

During one of my late-night iPhone scrolling sessions, I was delighted to come across the field of household archaeology, the study of homes and how we live in them, which is a companion to material culture, which is quite literally the study of our stuff.

I’m no household archeologist, but I’m the granddaughter of a Depression Era Midwesterner Who Kept Everything. A millennial pack rat. A keepsake queen. A connoisseur of collecting.

Nostalgia is my drug of choice, and it seems as though I’m powerless to the Endowment Effect, the explanation for why we value things that we own so much more than things that we don’t.

I’m proud of myself for getting rid of quite so much of that stuff during the past two months through Buy Nothing, but there’s still so much left to sort through and unpack. If I kept such a tedious collection of my own school work and kid art, can you imagine the boxes I have containing what’s left of my own children’s childhoods?

But rather than take you on a tour of those physical objects — aka material culture — I want to show you a piece of household archaeology that I want to remember.

When I first moved into my old house, it was a shade of country pink that I never wanted to see again, so I painted every surface, thinking I could somehow start fresh.

But to get this same house ready to rent, I had to revisit all those walls and baseboards and doors, and everywhere I turned, I saw little hints of that dreadful pink. Spots that reminded me of the previous owner and the many years he lived in what had become my home.

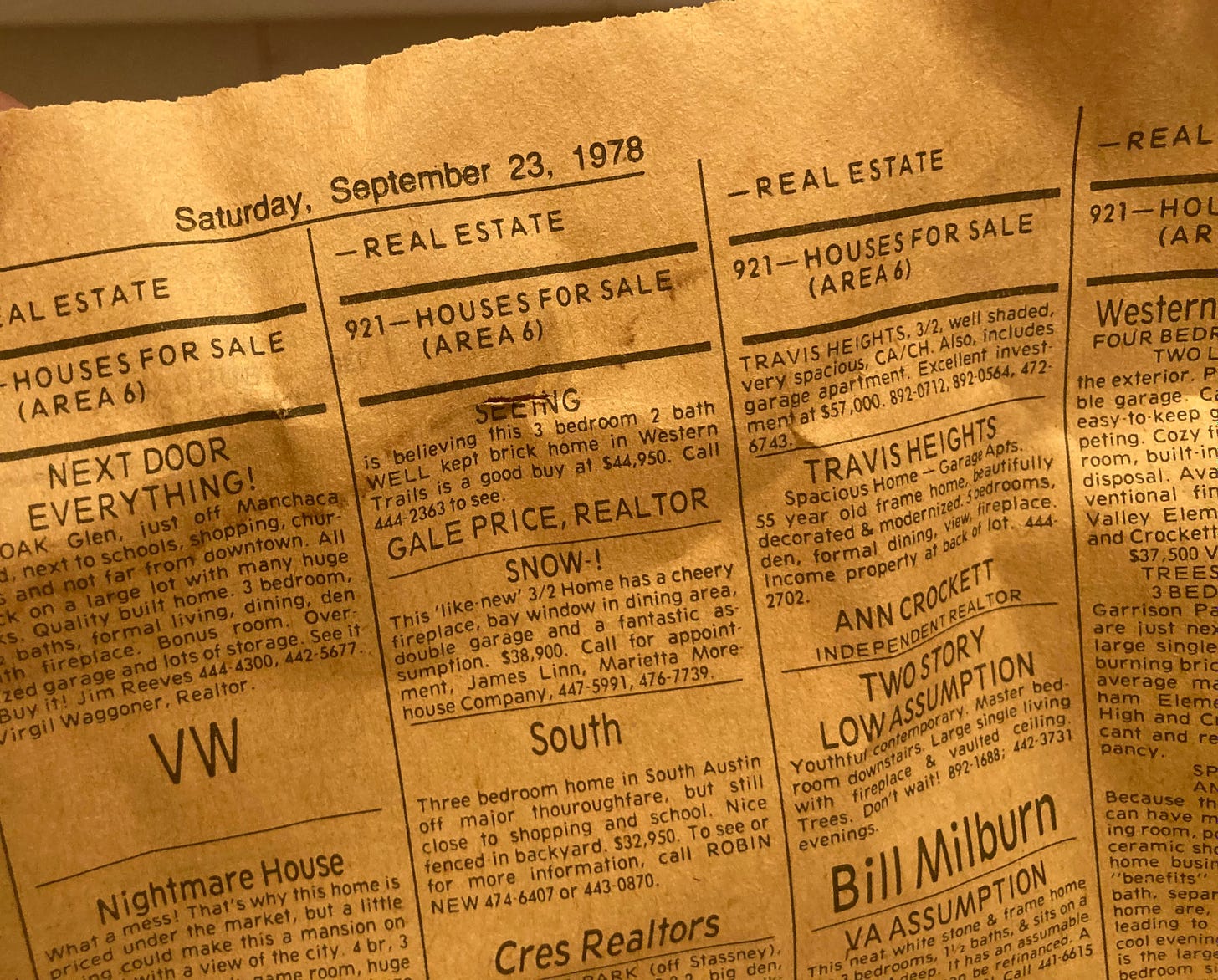

When Frank and my Uncle Carlos pulled out the old bathroom cabinet, not only was there more pink, we found a textured wallpaper that last saw the light of day during the Carter administration.

I know that because of a classified section of the Austin American-Statesman that was buried between the cabinet and the wall.

Garage sales, real estate listings, appeals for used music instruments.

A physical analog of what we now experience almost entirely online. A snapshot of a single, unremarkable day. A piece of yellowed newspaper that either belongs in a museum or a trash can.

We think we can scrub a a house of these fingerprints of former residents, but a house doesn’t forget that easily.

But, do we want a house to forget us? Do we want our past to stay in the past?

Or are we, even as we move from one place to another, leaving a trail of breadcrumbs that leads to a special place, even if we can’t go there?