What does it mean to have a sense of place?

The late architect Charles Moore, a founder of postmodernism, wanted us to look differently at the idea of place and placemaking.

It was 20 years ago this year that I came to Austin and decided to stay.

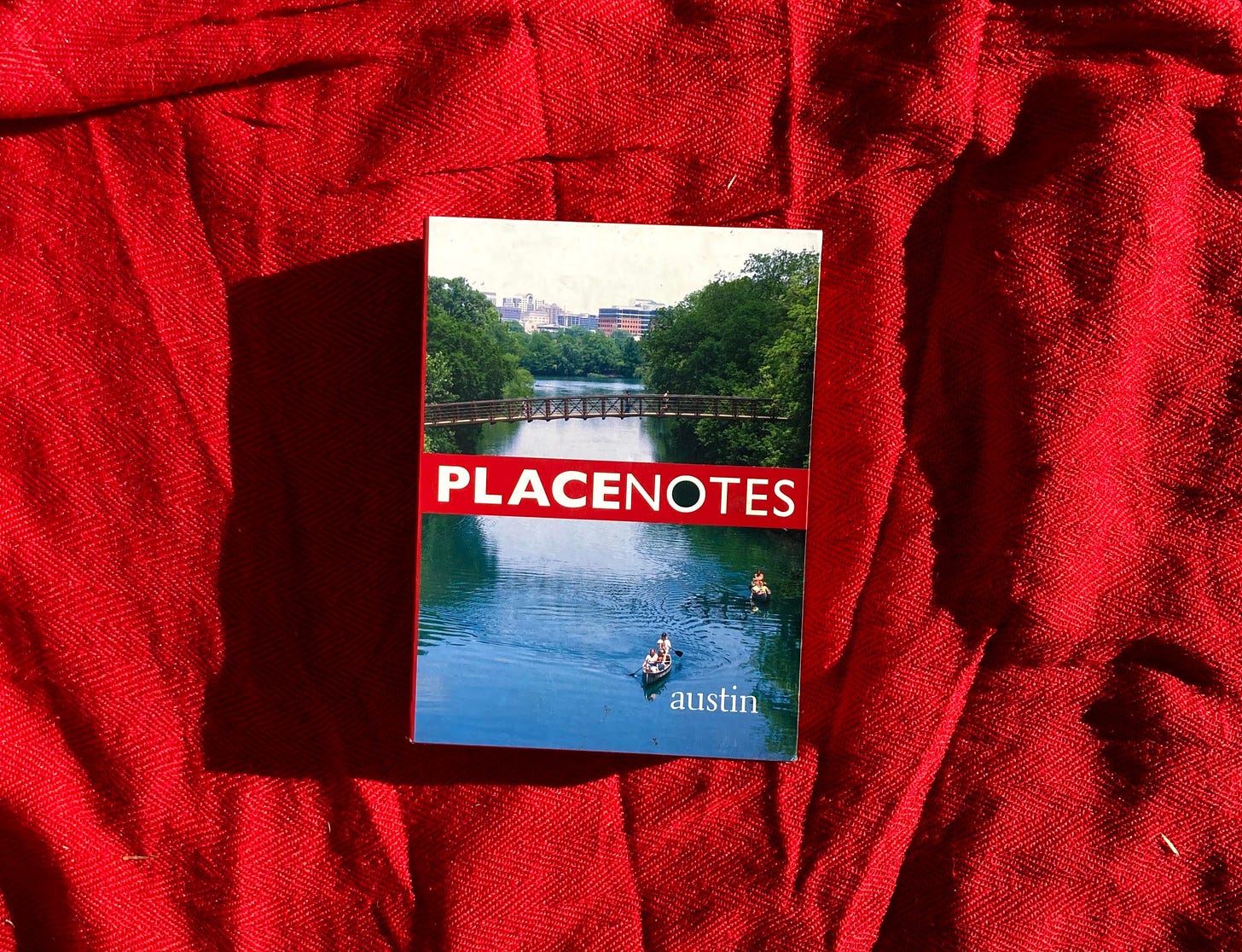

That summer, I received Placenotes: Austin, a “travel guide in a box,” as a welcome gift. Each of the 45 cards in the set featured a notable place in Austin and the history behind it.

For a new Austinite, this deck of cards offered a crash course in the city. I practically memorized the cards, learning about the Driskill Hotel and Laguna Gloria and the Elisabet Ney Museum, as well as the newer places like the Hotel San Jose and Central Market that also felt unique to this country mouse who had just moved to the city.

I started to understand Austin culture through this box of cards. I learned about the places that people loved enough to preserve and the newer additions to the city that had already shaped it in similar ways.

Published by the University of Texas Press, Placenotes was the first in a small series of boxed sets from the Charles W. Moore Center for the Study of Place. (It was edited by Kevin Keim, who is still the director of the Charles Moore Foundation.)

I remember reading that all those years ago and feeling a lightbulb go off.

The study of place.

I was a recent college graduate, filled with new ideas about the world, and I’d never not once considered that you could study place as a concept.

But here I was, in a city that was most certainly a place, getting ready to embark on a new adventure, one that is somehow now crossing into its third decade.

All these years later, I still have my Placenotes cards, and my curiosity about Charles Moore and his ideas about places has only grown as I’ve gotten older and spent more time thinking about the intersection of art, culture, and philosophy.

I’ve written about Charles Moore several times over the years, most notably in a 2021 article for Texas Monthly titled “Don’t Just Cook Dinner. Be the Architect of Your Meals” that looks at his “principles of place” through the eyes of food.

But those principles of place keep coming up, and I wanted to share them again.

(I’m also working on a story for next week about Marfa’s sense of place and Donald Judd’s essay, “Specific Objects,” which he published in 1964, the same year Moore published these principles in his oft-cited piece, “You Have to Pay for the Public Life.”)

So, what’s the connection between Charles Moore, who is best known for his work on California’s Sea Ranch — a utopian community of buildings that all have the same simple, rustic, weathered look that is now called “Sea Ranch style” — and Austin?

Moore lived the last decade of his life in Austin, teaching at the University of Texas at Austin from 1985 until his death in 1993.

By this point, his pioneering work in placemaking had led him to being called the father of postmodernism, a design philosophy that, generally speaking, shifts the focus from form to function.

This was the hook that allowed me to write about Charles Moore and food. I argued that because we had a “modernist cuisine” movement a decade ago, we were entering a post-modern era, where Moore’s principles of design would apply.

“Modernists are beholden to no traditions. Postmodernists embrace them,” I wrote, thinking about the difference between molecular cuisine and the more “real life” (and family history-informed) foods that are en vogue today.

These days, I think about the sense of place with so many things beyond food.

So, here are Charles Moore’s five principles of design:

1. “Bread cast on water come(s) back as club sandwiches.”

What we put into things, we get back tenfold. Putting effort into things makes them more valuable. If you make the bread, you appreciate the sandwich. If you make the dining room table, you’ll reap the benefits of that labor for much longer than it took for you to make it. This is Moore’s way of saying that a building will take care of its occupants if its occupants take care of it. If we take care of our neighbors, the whole neighborhood takes care of us.

2. “If buildings are to speak, they must have freedom of speech.”

Do you believe that everyone has something to say? Do you believe that everyone should be heard? Do you believe that you must agree with what they say for it to be important? This seems like a contradiction from Moore, who was one of the architects behind Sea Ranch, a community that has some of the strictest rules found in any HOA in the country, but Moore is advocating here for letting the needs of the building (and the environment) outweigh those of the individual personalities building them. He is also telling us to maintain some distance between who we are and the art we make. Sometimes, our art says things that we cannot or are not yet ready to say. And that is the kind of art that challenges the status quo and our established ideas about the world.

3. “Buildings must be inhabitable by the bodies, minds and memories of humankind.”

Humans wouldn’t exist as we do today without buildings, and those buildings connect us to our humanity and to our history. And yet, buildings wouldn’t exist without humans. These structures, tell a story, but they also become part of that story. This principle forces us to always remember that buildings are for people and for those people, life is for living. Anything that has a strong sense of place should remind us of our mortality. Sometimes we outlive buildings, but often, they outlive us.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Invisible Thread to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.