A menacing force that just won't go away

One of the country's biggest — and most hateful — newspapers was once published in my small Missouri hometown. The paper folded 100 years ago, but its ideals persist.

There’s a haunting reason why there are so many train tracks in Aurora.

When I was a kid growing up there, I didn’t think twice about the wide stretch of train tracks that separated my side of town from the north side of town, a geographic and cultural divide based on class, not race, because there weren’t enough families of color to fill a neighborhood block.

When I was a kid, the train still ran, blowing its horn, politely but persistently, throughout the night. It still comes and goes at all hours of the day, carrying grain, waste, and whatever they make in the dog food flavoring factory whose smell gives the town an eau de burnt cheese casserole.

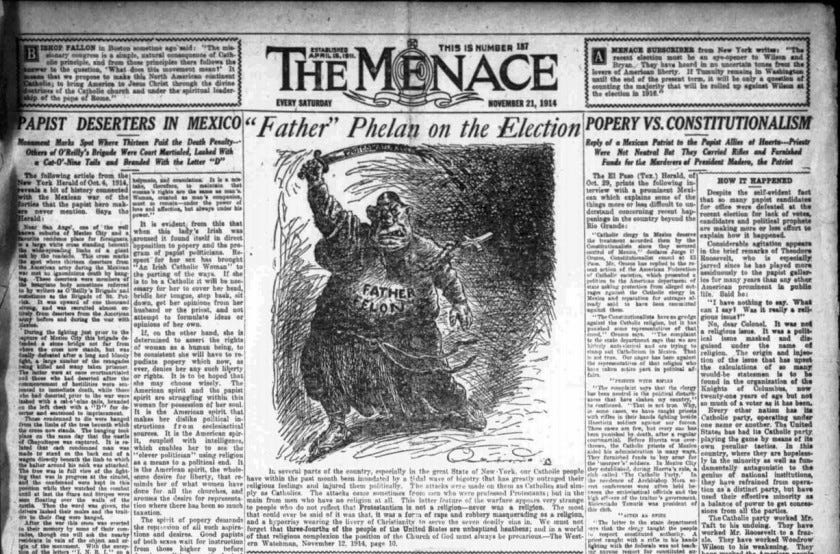

But in the 1910s, those trains carried something else: Copies of The Menace, an anti-Catholic newspaper that at one point during its short incarnation had 1.5 million subscribers, far more than the daily papers in New York City.

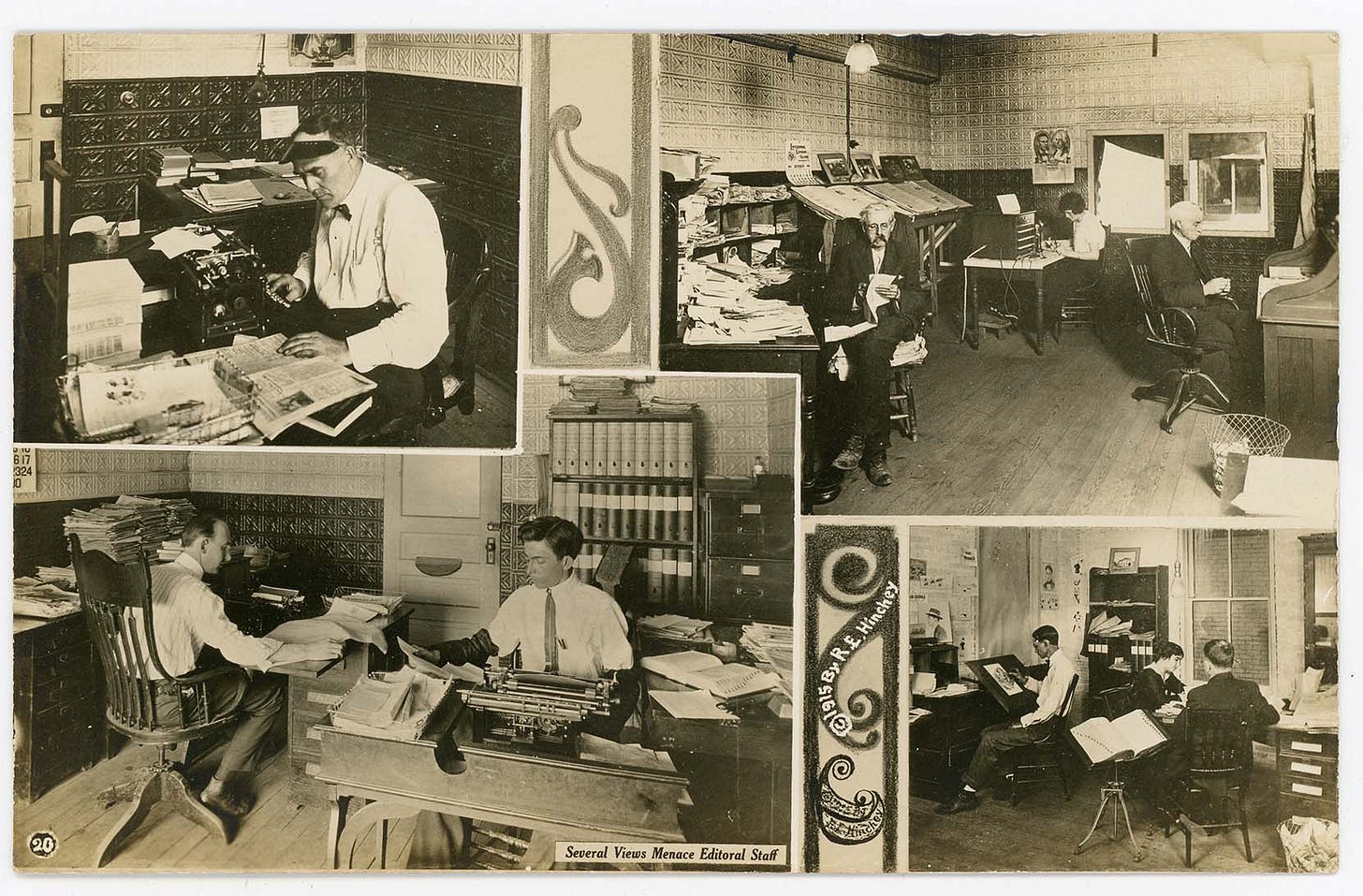

The paper launched in 1911 in an old opera house with 22 subscribers, but within three years, it reached a million people around the country every week. Aurora had 4,000 people at the time, down from a peak of 15,000 during the area’s mining boom.

At their printing facility, Phelps and McClure, whose names still grace the streets of Aurora, published other books and pamphlets that stoked fears that the Catholic Church was enslaving women in convents, hoarding weapons, and being controlled by church officials in Rome.

According to the State Historical Society of Missouri, The Menace was so popular in the 1910s that the post office in Aurora established a railroad substation to handle its circulation.

For the first few years, the Catholic Church ignored the paper. By 1916, it had grown so large and influential that the Knights of Columbus sued The Menace for slander and libel. That summer, The Menace won a federal obscenity trial in nearby Joplin, and after the trial, the editors arrived by train to enormous crowds of supporters.

Then World War I happened, and Americans found a new menace: Germans. The newspaper’s subscriptions fell off almost as quickly as they rose. By the end of the year 1919, the paper closed after another fire. The building was lost, and the mailing list was the only item saved from the flames.

With that mailing list, they started the New Menace in April 1920, first in Branson and then, in 1922, moved it back to Aurora. This was when the Ku Klux Klan, which is where many fervent anti-Catholics found themselves, was also on the rise. The paper would defend the actions of Klansmen throughout its run until 1931 when it closed for good.

I didn't know about this newspaper as a young journalist working at my hometown paper in high school. Or if my bosses told me about it, the gravity of the history didn’t sink in until 2015, when Matt Pearce, a writer for the LA Times, wrote about The Menace. (He was writing about American religious intolerance in response to the shooting at the synagogue in Kansas City, where a man from near Aurora killed three people in a hate crime.)

In the article, he quotes Justin Nordstrom, an associate professor of history at Penn State Hazleton who studied The Menace, who explained that the paper “begins a kind of tidal wave, a journalistic explosion that sweeps the entire country.”

The quiet hateful thoughts became out loud hateful thoughts.

In 2015, Mary Strickrodt, then president of the historical society, questioned why the paper had become so popular. “Why are people so quick to find people to hate? To be bigger than?”

She pointed out that the newspaper employed many people, which made people view them favorably. And the ideas themselves didn’t seem intolerable to the people who held them.

Sadly, those ideas aren’t all that different from the ideas we hear in politics today.

In the obscenity trial, The Menace argued that it was fighting to save American democracy. It became clear, over the years, that the anti-Catholic ideas coming from the paper were sourced from writers who weren’t living in areas where Catholics lived, and they “preyed on the ignorance of their populations,” according to historian Christopher S. Saladin.

The Catholic Church, with its headquarters in Rome, was synonymous with big cities, where people lived in close quarters and mixed communities. Nordstrom said that they feared losing the “pastoral values” of rural America, and this fear stoked Americans’ long-held sense of nativism and a fear of outsiders.

Small towns like Aurora were the opposite of those places where modernity flourished. Not everyone had electricity or running water, and women didn’t wear pants and had short hair.

In many ways, it was a widening of the rural-urban divide that we see today.

Soon after The Menace disappeared, its memory faded away, and the town of Aurora lost its national fame as a bastion of Catholic xenophobia.

But it’s not difficult to see how nationalism, fear of foreigners, and resistance to cultural change are as prevalent as ever. Catholics have been replaced by Muslims, queer people, immigrants seeking a better life.

Sadly, as history tells us, one election isn’t going to change any of that.

Happy Halloween, readers.

I wanted to share this story today for obvious (and very scary) reasons, but I also wanted to share it because it allows me to show what it has been like to sit in discomfort with issues that are much bigger than any one person.

I’ve been wrestling with The Menace for a decade now, and I can’t say that it’s gotten any easier. But loving people (and places) that I struggle to understand is a challenge I’ve grown familiar with.

Eight years ago, this gargantuan task was enough to make me lose my mind.

Now, it helps me find my center.

We are all complex.

We all contain contradictions that don’t make sense to others.

We all have ghosts in the train depot.

I needed to write about mine.

I hope you’ve voted already, if you can, and that you are looking in your own closet and, more importantly, your toolbox. No matter what happens next week, we are all going to need all the tools we have.

I’m working the polls on Election Day next week, so I’m going to re-share a post I wrote when I first started doing that work. I’ll be back with a new column soon.

Sending my best and my gratitude for all of your subscriptions and your support.

Until next time,

Addie

Thank you for shedding a light on this little-known piece of history, Addie. I am thinking a lot about the role of media in shaping the cultural narrative these days, and this is a fascinating piece to the puzzle.

I hope with all of the things going on in Aurora that we will be known for its progress and forward thinking. Thanks for the history lesson that I doubt many people are aware of. The tracks are still a reminder of the have and have nots of the past, but hopefully will diminish with time as well.