No wonder this is still the hottest ticket in D.C.

Seeking out Black history wherever we go, but especially at the Smithsonian.

You don’t have to go to Washington D.C. to visit an excellent museum about Black history and culture, but if you’re in D.C., you shouldn’t miss the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

When it opened in September 2016, the NMAAHC represented more than 40 years of advocacy and effort from lawmakers, as we know, who rarely agree on matters of race, public education and taxpayer funding.

I’ve always been a bit of a Smithsonian nerd, so this museum caught my attention when it opened, especially because of its striking architecture — a five-story inverted crown made from rusting cast-aluminum panels that doesn’t look much like anything else in D.C.

The Smithsonian museums I remembered from those visits as a kid looked a lot like the neoclassical and brutalist federal buildings all along the mall. In those days, the Air and Space Museum was the “new” museum, even though it had been open since the 1970s. This was the era when having a museum dedicated to Black Americans was controversial enough that one obstinate politician after another could insert a hurdle that required another 10 or 15 years to overcome.

The Museum of the American Indian opened in 2004. The African American history museum wouldn’t break ground for another 8 years.

In 2017, my mom and I flew into the nation’s capital for my Uncle Jack’s big birthday celebration, but the newly opened NMAAHC was still relatively hard to get an entrance ticket, so I didn’t try to squeeze it in.

Six years later, this museum continues to draw more than a million visitors a year, and tickets are still hard to come by.

This fall, I decided to visit Uncle Jack just a few days before his 96th birthday, and there was no way I was going to go to D.C. again and not see this museum. (And the Museum of the American Indian, which I’ll save for a separate post.)

I got my ticket through the museum’s online “walk up” ticket queue, which is the only way to visit the NMAAHC if you haven’t made reservations weeks in advance. (Like all the Smithsonian museums, this one is free, but they have to regulate the rate of entry because the galleries get so crowded.)

Visitors are recommended to start in the basement where the entire history of slavery unfolds, first in narrow hallways that mimic the cramped experience of being on a ship, through bigger open rooms that go through the civil rights era into the modern social justice movement.

Curators are sensitive to the fact that people of all ages visit the museum, but they don’t shy away from the pain and suffering that has been part of the Black American experience for more than 400 years.

The first five floors could function as a standalone museum, but there are another five floors of above-ground gallery space where you’ll find permanent exhibits dedicated to pop culture and sports icons, politicians and freedom fighters. There’s a genealogy center and a cafeteria.

It would take weeks to experience everything in this museum — it’s absolutely stunning the amount of information they are able to share under one roof — so at some point, I had to relinquish my completist tendencies and simply enjoy being there.

I spent all day wandering around this epic monument to Blackness and appreciated learning what I could about the sweeping influence of Black culture and the notable figures whose contributions, from leading abolitionist uprisings to writing hip-hop lyrics, are long overdue under the distinguished spotlight of the “Nation’s Attic.”

I was reminded often of the National Museum of African American Music in Nashville, where curators tell an equally compelling story through a mix of historical artifacts and multimedia.

One of the highlights of the entire museum is a special exhibit on Afrofuturism that will be on display until August of 2024. (Readers, this gives you enough time to plan a trip!)

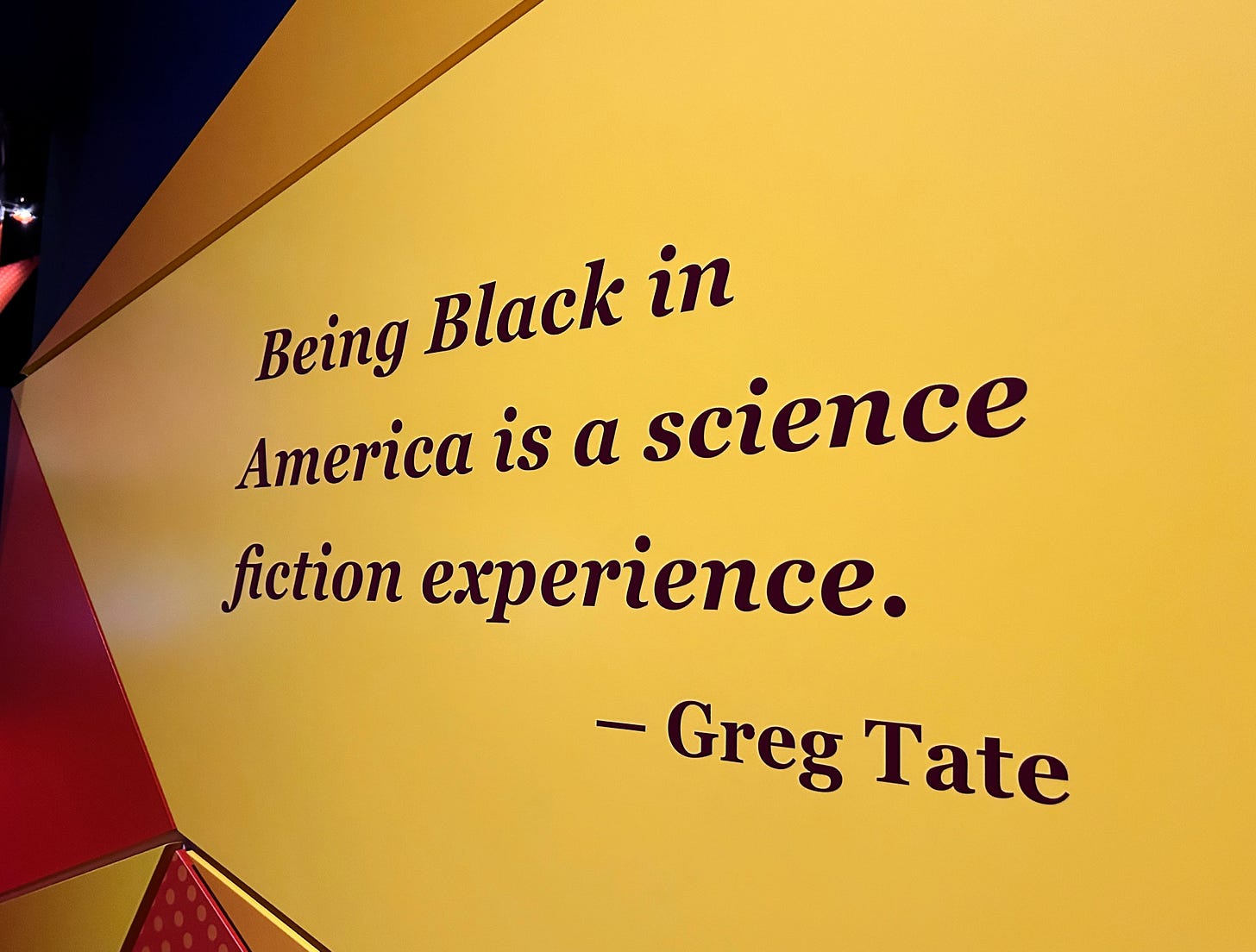

Afrofuturism is “the ability to imagine or speculate alternative futures, ones that are drastically different from the present realities” and this “allows Black people room for liberation and the freedom to see life differently.”

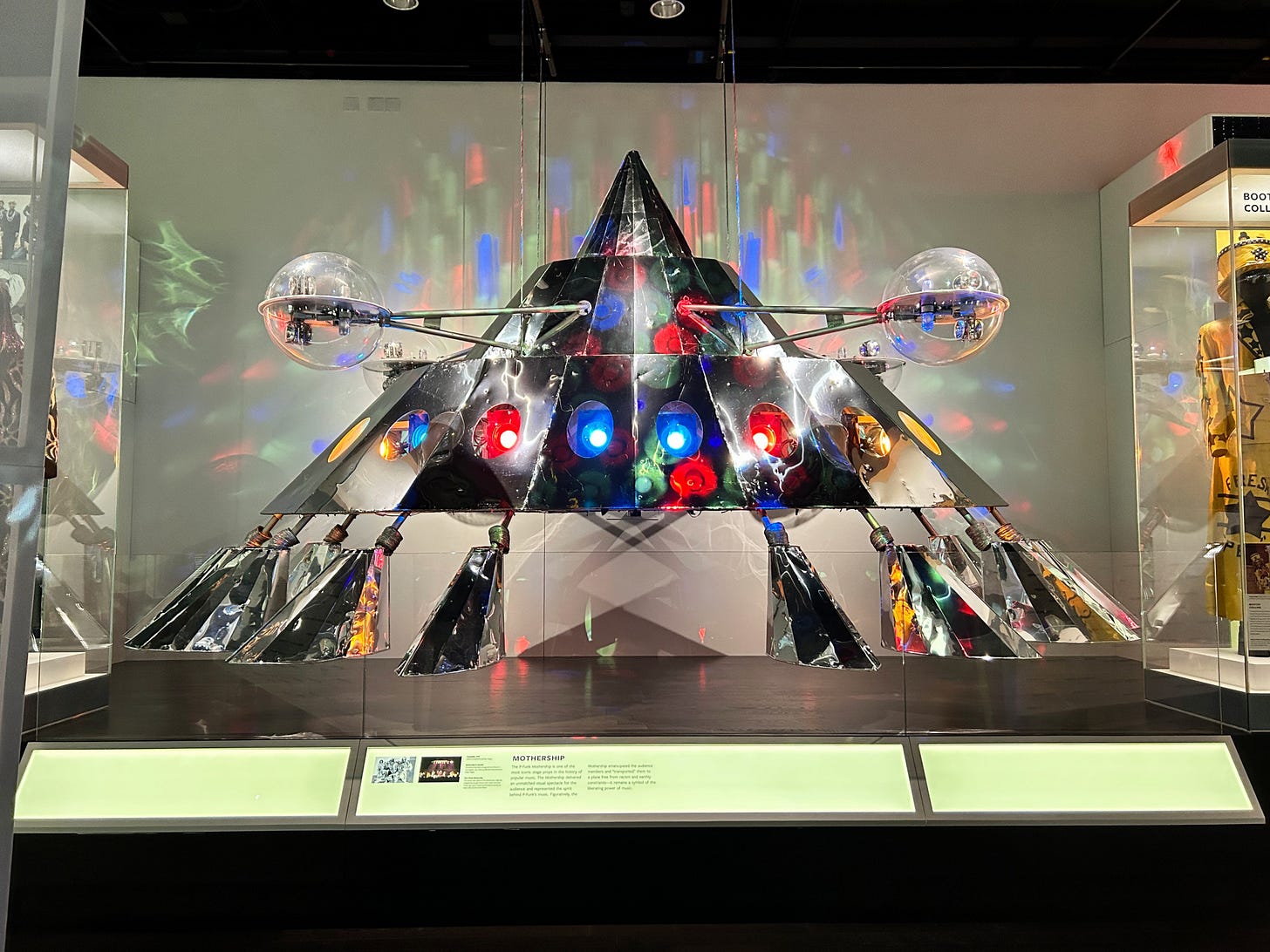

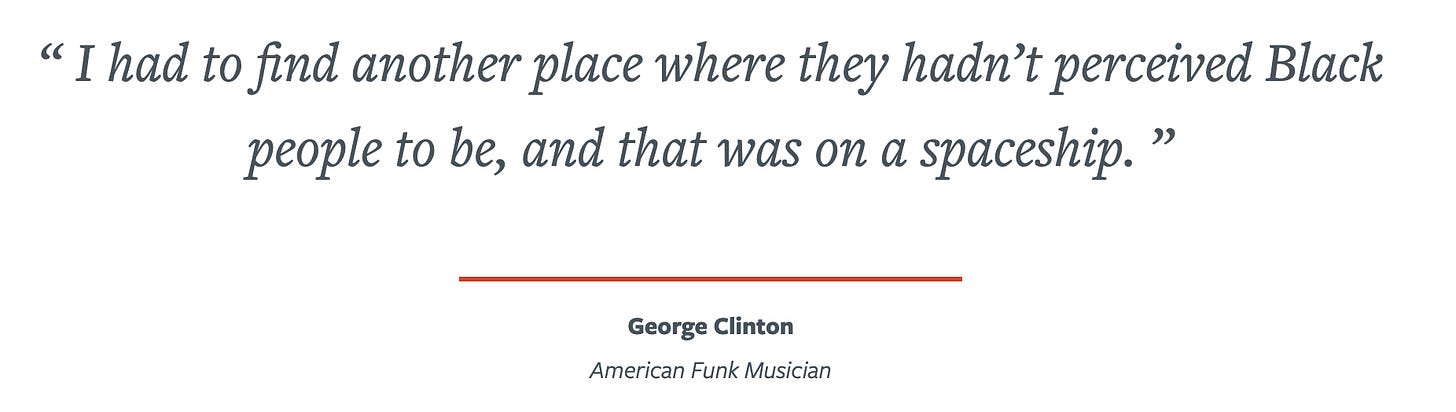

In other words, come for the P-Funk Mothership and stay for the Octavia Butler’s typewriter.

Throughout this temporary exhibit (that really should be permanent), visitors learn about how and why technology and our collective ability to re-imagine a new, more equitable future has played a role in the civil rights and social justice movements. The exhibit touches on everything from Black Panther’s Wakanda to Henrietta Lacks, whose “immortal” cells have made modern medicine possible.

In this one section of the museum, you could spend a couple of hours soaking up the videos and plaques that tell a story that feels like one of the most culturally relevant conversations happening in American today.

Each time I visit a museum like this one, my perspective widens beyond what I’ve learned about from white-dominated spaces and what I have experienced as a white cis woman growing up in the Midwest.

And the more of these cultural history museums I visit, the more important I realize it is to take what I learn in books, TV and social media and head to a curated space, like a museum, where I can have a fully immersive educational experience.

Until now, I’ve never been the type of person to travel to another city specifically to see one museum, but this past year, with visits to the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City and the National Museum of African American Music in Nashville, has tipped the scales and turned me into that kind of person.

I can now clearly see that if we have the privilege to be able to travel, then we have an obligation to expand our understanding of cultures outside our own by going to museums like this one so we can learn things that we take back home with us.

More than 1.6 million people visited this museum last year. That’s the eighth most visited museum in the country, and it thrills me to think that so many thousands of people are going through it every day.

That’s a lot of people like me re-learning history and a bunch of people who already know this history, in part because they’ve lived it, saying, “Finally.”

Up next: More adventures in Washington D.C.